Metropolitan Correctional Center

by guest author Matt Crawford

Mies and his followers believed that the steel-and-glass box was not just for corporate office towers, but that the form held the promise of a “universal space” that could house any function. The adaptability of the steel and glass box is demonstrated by the Heating Plant (1961) at O’Hare Airport and the “God box” or Saint Savior’s Chapel (1952) at IIT. Yet if there is one building type that defies enclosure in thin glassy planes it must be a jail.

Higher crime rates, increased prison crowding and riots, most famously at Attica in 1971 which left thirty-nine dead, compelled the Federal Bureau of Prisons to build 66 new correctional facilities between 1968 and 1978. Never fashionable in architectural circles–or any circles–prisons and jails became attractive to architects in the 1970s for a number of reasons, not the least of which was the lack of commissions during the economic recession of the early 1970s.

Part of the Federal program was the construction of Metropolitan Correctional Centers (MCC’s), a new type of detention facility for those awaiting trial or serving short sentences. Conceived of as a demonstration project by the Bureau of Prisons, the minimum-security MCC’s were to offer more humane conditions for inmates, and Chicago was one of five cities selected for one in 1970.

As soon as the building’s location at the corner of Clark and Van Buren (71 W. Van Buren St.) was announced, a coalition of loop banks and civic organizations filed a lawsuit to halt the project fearing that the jail would drive down property values. Though the suit failed, it revealed the almost universal opposition to jails by the people who have to look at them. The Bureau of Prisons certainly anticipated the public resistance and the guidelines for the MCC program required that the new jails enhance and protect the character of their urban surroundings.

Harry Weese & Associates were chosen as architects for the new MCC in Chicago in 1972. Harry Weese brought to the project the then-waning modernist ideal that the architect had a moral imperative to ease social ills, and he embraced the challenge of designing a jail which would be decent for the detained and a dashing addition to the Loop.

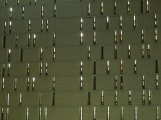

Plan of inmate floor with cells arranged around perimeter. Source: Ray, Leah. “Opposing Mies.” In Chicago Architecture: Histories, Revisions, Alternatives.

The assertive 27-story tower was completed in 1975. As he did in many of his other designs Weese employed simple geometric forms, in this case the prism-shaped tower rises from a triangular plan. The form reduces the overall mass of the building to such a degree that it presents the illusion of a two-dimensional plane without sides when viewed from the sharp corners.

The taught exterior walls are constructed of slip-form cast concrete. There is none of the compulsive detailing of Mies, holes left by the form tie-bolts were left unfilled and subtle imprints in the concrete surface created by the formwork were left as is. The seemingly random trapezoidal panels at the corners of the second and ninth floors are covers for the jacks for the post-tensioned concrete floor plates; the architect let the trapezoidal shape of this equipment guide the shape of the cover panels. In its original design, the concrete exterior walls were raw concrete; the current light tan paint was a jarring change for many when it was applied to the exterior following repairs in 2006.

So much of the character and interest of the building comes from its slit windows which perforate the façade in a random and lively pattern. It was Weese himself who first made the very apt comparison of the façade to an IBM computer punch card. The windows on the upper floors which illuminate inmate cells are 5 inches wide, the maximum width allowed by the Bureau of Prisons. (Interior bars were added to these in 1985 after a pair of inmates enlarged one of the openings with a barbell and rappelled down the e xterior on an extension cord to temporary freedom.) Staff offices on the lower floors are distinguished by the wider windows. All of the openings are splayed, improving the view angle from the interior as well as hinting at the arrow loops found in medieval fortifications.

xterior on an extension cord to temporary freedom.) Staff offices on the lower floors are distinguished by the wider windows. All of the openings are splayed, improving the view angle from the interior as well as hinting at the arrow loops found in medieval fortifications.

The jail was designed to hold 440 inmates, but they are separated into self-contained modules of 44 people. Each module consists of two floors with single-room cells arranged around the perimeter of the plan. At the center of the plan is a double height common area, as well as a station from which a single guard can keep watch on the perimeter cells. This architectural relationship between the keeper and the kept works much like Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon prison design of the eighteenth century, as well as the nurse-patient arrangement at Prentice Hospital.

Like many Chicagoans, I take great pride in our beautiful buildings, and I love to tell out of town friends interesting little facts about them. I think that’s why I’m so fond of this blog. Mr. Crawford’s above piece is excellent, and you know that I’ll be telling people about the (temporary) escape from the center.

Glad you liked the piece. I glossed over the escape which was founded on a brilliant ruse that reminds me of the Trojan Horse story. The story goes that the two gentlemen were at a maximum security prison when they hatched a plan to escape from that institution. When their plot was discovered they were offered a deal to come to Chicago to tell their story to the feds so that future plots might be foiled. They must have been pleased to find that their accommodation would be at a minimum security jail without bars. They made their move at night during a thunderstorm, though it seems odd that no one heard them hammering away at the concrete.